Experiments in polyphonic music in the late Middle Ages, where several melodic lines were performed simultaneously in contrast the monophony of Gregorian chant, formed the principal influence in the development of the new musical style of the Renaissance. In addition, there was a renewed study of the Classical Latin language, influencing composers to create music that closely fit the meaning and rhythm of the text. The humanist ideal of the Renaissance also had some effect on the creation of music: in addition to its function of praising and giving glory to God, music as a means of lifting the human spirit, and conveying the sacred texts intelligibly and expressively became an important consideration for the composer. Another important factor was the invention of printing, which allowed new compositions to spread widely and quickly. Gregorian chant was still widely performed throughout the Renaissance. Printed editions of the traditional Gregorian repertoire began to appear for the first time around 1473. New insights into the Latin language lead to some editing of the traditional chant repertoire: important melodic phrases were often shifted from the grammatical endings of words to more important syllables. This was thought of as a “correction” rather than a deformation of the chant tradition.

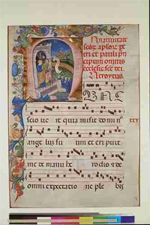

Gregorian chant Gradual page, 15th Century Italy From Columbia University. Click on image for larger view.

The early Renaissance style of polyphony was developed by a group of composers living in an area that includes modern day Netherlands, Belgium and parts of France. This “Netherlandish” School is represented by the compositions of Johannes Ockeghem, Josquin des Prez, Jacob Obrecht, Nicolas Gombert and Jacob Clemens, also known as “Clemens non Papa.”

Missa Ecce Ancilla Domini by Johannes Ockeghem From the Vatican Library

They composed settings of the Mass Ordinary and Motets, compositions used to replace the Gregorian propers of the Mass and office Responsories. Like the polyphony of the Middle Ages, they often used melodies from Gregorian chant as thematic material for their compositions, but they also created music from entirely new material, and not infrequently composed Mass Settings based on secular tunes, the so called “Parody Masses.”

Unlike Medieval Polyphony, where the different voices often have distinctive melodies and rhythmic movement, the Renaissance composers preferred to write a style of polyphony where each voice was of equal importance and similar in style and movement. Four-voice compositions predominate, intended to be performed by singers without accompaniment. Imitation and canon are frequent compositional techniques, where dissonances are carefully prepared and resolved. The resulting vertical sonorities are predominately triadic; the rhythmic movement is fluid, often arising from the text, imparting a very suave and pleasant motion of the voices.

The popularity of the Netherlandish style of composition spread all over Europe, aided by the dissemination of printed part books. This inspired composers in Italy, France, England, Germany and Spain to create their own polyphonic compositions. For the first time, national schools of compositional style began to emerge, as exemplified by the works of Cristobal Morales, Christopher Tye, Thomas Tallis, William Byrd, Orlando de Lasso, and Jacob Arcadelt.

In the late Renaissance, the emergence of the Roman school brought polyphonic composition to its highest maturity as exemplified by Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, and the Spaniard, Tomas Luis de Victoria. Palestrina worked out a system of polyphonic writing that is used to this day as a model of counterpoint. Even late in the Renaissance, the Gregorian melodies were still used extensively as bases for polyphonic compositions. The melodic flow and rhythmic suppleness of the melodic lines of Palestrina show an unmistakable kinship to traditional chant. His compositions show an eloquent sensitivity to the meaning and structure of the text while avoiding any theatrical excess.

Credits

Joseph Metzinger

- Back to Top -